Leaving the European UnionBritain faces up to Brexit

As long as the government stays in denial about Brexit’s drawbacks, the country is on course for disaster

CRISIS?

What crisis? So many have been triggered in Britain by the vote a year

ago to leave the European Union that it is hard to keep track. Just last

month Theresa May was reduced from unassailable iron lady to

just-about-managing minority prime minister. Her cabinet is engaged in

open warfare as rivals position themselves to replace her. The Labour

Party, which has been taken over by a hard-left admirer of Hugo Chávez,

is ahead in the polls. Meanwhile a neurotic pro-Brexit press shrieks

that anyone who voices doubts about the country’s direction is an

unpatriotic traitor. Britain is having a very public nervous breakdown.

The chaos at the heart of government hardly bodes well for the exit negotiations with the EU, which turned to detailed matters this week and need to conclude in autumn 2018. But the day-to-day disorder masks a bigger problem. Despite the frantic political activity in Westminster—the briefing, back-stabbing and plotting—the country has made remarkably little progress since the referendum in deciding what form Brexit should take. All versions, however “hard” or “soft”, have drawbacks (see article). Yet Britain’s leaders have scarcely acknowledged that exit will involve compromises, let alone how damaging they are likely to be. The longer they fail to face up to Brexit’s painful trade-offs, the more brutal will be the eventual reckoning with reality.

As the scale of the task has become apparent, so has the difficulty of Britain’s position. Before the referendum Michael Gove, a leading Brexiteer in the cabinet, predicted that, “The day after we vote to leave, we hold all the cards.” It is not turning out like that. So far, where there has been disagreement Britain has given way. The talks will be sequenced along the lines suggested by the EU. Britain has conceded that it will pay an exit bill, contrary to its foreign secretary’s suggestion only a week ago that Eurocrats could “go whistle” for their money.

The hobbled Mrs May has appealed to other parties to come forward with ideas on how to make Brexit work. Labour, which can hardly believe that it is within sight of installing a radical socialist prime minister in 10 Downing Street, is unsurprisingly more interested in provoking an election. But cross-party gangs of Remainer MPs are planning to add amendments to legislation, forcing the government to try to maintain membership of Euratom, for instance, which governs the transit of radioactive material in Europe. Even within the government, the prime minister’s lack of grip means that cabinet ministers have started openly disagreeing about what shape Brexit should take. Philip Hammond, the chancellor, has been sniped at because he supports a long transition period to make Brexit go smoothly—a sensible idea which is viewed with suspicion by some Brexiteers, who fear the transition stage could become permanent.

The

reopening of the debate is welcome, since the hard exit proposed in Mrs

May’s rejected manifesto would have been needlessly damaging. But there

is a lack of realism on all sides about what Britain’s limited options

involve. There are many ways to leave the EU, and none is free of

problems. The more Britain aims to preserve its economic relationship

with the continent, the more it will have to follow rules set by foreign

politicians and enforced by foreign judges (including on the sensitive

issue of freedom of movement). The more control it demands over its

borders and laws, the harder it will find it to do business with its

biggest market. It is not unpatriotic to be frank about these

trade-offs. Indeed, it is more unpatriotic to kid voters into thinking

that Brexit has no drawbacks at all.

The government has not published any estimates of the impact of the various types of Brexit since the referendum, but academic studies suggest that even the “softest” option—Norwegian-style membership of the European Economic Area—would cut trade by at least 20% over ten years, whereas the “hardest” exit, reverting to trade on the World Trade Organisation’s terms, would reduce trade by 40% and cut annual income per person by 2.6%. As the economy weakens, these concerns will weigh more heavily. Britain’s economy is growing more slowly than that of any other member of the EU. The election showed that its voters are sick of austerity. Our own polling finds that, when forced to choose, a majority now favours a soft Brexit, inside the single market (see article).

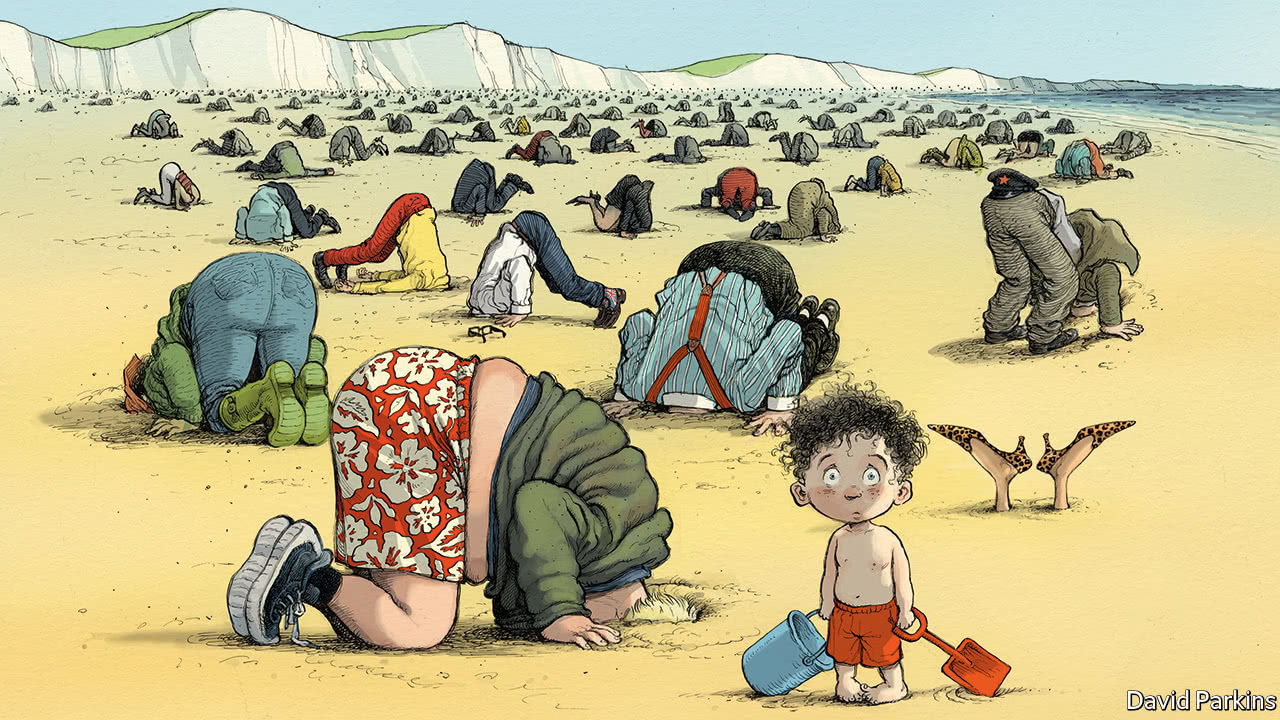

So it is all the more crucial that all sides face up to the real and painful trade-offs that Brexit entails. The longer Britain keeps its head in the sand, the more likely it is to end up with no deal, and no preparations for the consequences. That would bring a crisis of a new order of magnitude.

The chaos at the heart of government hardly bodes well for the exit negotiations with the EU, which turned to detailed matters this week and need to conclude in autumn 2018. But the day-to-day disorder masks a bigger problem. Despite the frantic political activity in Westminster—the briefing, back-stabbing and plotting—the country has made remarkably little progress since the referendum in deciding what form Brexit should take. All versions, however “hard” or “soft”, have drawbacks (see article). Yet Britain’s leaders have scarcely acknowledged that exit will involve compromises, let alone how damaging they are likely to be. The longer they fail to face up to Brexit’s painful trade-offs, the more brutal will be the eventual reckoning with reality.

Latest updates

Winging it

In

the 13 months since the referendum, the awesome complexity of ending a

44-year political and economic union has become clear. Britain’s

position on everything from mackerel stocks to nuclear waste is being

worked out by a civil service whose headcount has fallen by nearly a

quarter in the past decade and which has not negotiated a trade deal of

its own in a generation. Responsibility for Brexit is shared—or, rather,

fought over and sometimes dropped—by several different departments.

Initially Britain’s decision not to publish a detailed negotiating

position, as the EU had, was put down to its desire to avoid giving away

its hand. It now seems that Britain triggered exit talks before working

out where it stood. The head of its public-spending watchdog said

recently that when he asked ministers for their plan he was given only

“vague” assurances; he fears the whole thing could fall apart “at the

first tap”.As the scale of the task has become apparent, so has the difficulty of Britain’s position. Before the referendum Michael Gove, a leading Brexiteer in the cabinet, predicted that, “The day after we vote to leave, we hold all the cards.” It is not turning out like that. So far, where there has been disagreement Britain has given way. The talks will be sequenced along the lines suggested by the EU. Britain has conceded that it will pay an exit bill, contrary to its foreign secretary’s suggestion only a week ago that Eurocrats could “go whistle” for their money.

The hobbled Mrs May has appealed to other parties to come forward with ideas on how to make Brexit work. Labour, which can hardly believe that it is within sight of installing a radical socialist prime minister in 10 Downing Street, is unsurprisingly more interested in provoking an election. But cross-party gangs of Remainer MPs are planning to add amendments to legislation, forcing the government to try to maintain membership of Euratom, for instance, which governs the transit of radioactive material in Europe. Even within the government, the prime minister’s lack of grip means that cabinet ministers have started openly disagreeing about what shape Brexit should take. Philip Hammond, the chancellor, has been sniped at because he supports a long transition period to make Brexit go smoothly—a sensible idea which is viewed with suspicion by some Brexiteers, who fear the transition stage could become permanent.

The government has not published any estimates of the impact of the various types of Brexit since the referendum, but academic studies suggest that even the “softest” option—Norwegian-style membership of the European Economic Area—would cut trade by at least 20% over ten years, whereas the “hardest” exit, reverting to trade on the World Trade Organisation’s terms, would reduce trade by 40% and cut annual income per person by 2.6%. As the economy weakens, these concerns will weigh more heavily. Britain’s economy is growing more slowly than that of any other member of the EU. The election showed that its voters are sick of austerity. Our own polling finds that, when forced to choose, a majority now favours a soft Brexit, inside the single market (see article).

Back in play

A

febrile mood in the country, and the power vacuum in Downing Street,

mean that all options are back on the table. This is panicking people on

both sides of the debate. Some hardline Brexiteers are agitating again

for Britain to walk away from the negotiations with no deal, before

voters have a change of heart. Some Remainers are stepping up calls for a

second referendum, to give the country a route out of the deepening

mess. As the negotiations blunder on and the deadline draws nearer, such

talk will become only more fevered.So it is all the more crucial that all sides face up to the real and painful trade-offs that Brexit entails. The longer Britain keeps its head in the sand, the more likely it is to end up with no deal, and no preparations for the consequences. That would bring a crisis of a new order of magnitude.

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario